There is no way of knowing if your site is being browsed by people using screen readers. Aside from the fact that this could be a privacy concern, there is also a technological barrier. There is no way to determine that the site is being accessed by a screen reader because the screen reader accesses information from your browser, not the website. Your browser is a ‘user agent’ and information about your browser is available, but a screen reader is not a user agent. This means that it’s very difficult to estimate the size of the population of screen reader users or to identify trends in how they are using the internet.

WebAIM (Web Accessibility In Mind) is a non-profit organization based at the Center for Persons with Disabilities at Utah State University that is engaged in a mission to empower both web users with disabilities and creators of web content. One of their many projects has been collecting information about screen reader use through a periodic survey, then compiling the data and making it available on their site. WCAG 2.0 was released as a Final Recommendation was released in December, 2008 and the first WebAIM Screen Reader User Survey was conducted in January, 2009. In December, 2017, they published the data from Screen Reader Survey #7. Below is a quick summary of a few of the findings.

Survey Population

The survey is made available on the web in English only, and respondents located in North America, Europe/UK, and Asia made up over 90% of the 1,792 responses. The most recent survey had a higher number of respondents from outside of North America than surveys in the past. About 11% of respondents reported that they did not use a screen reader due to a disability. This subpopulation is likely to be primarily developers and testers, and when the responses of this group differed significantly from the overall responses, the report notes those differences.

Technologies

Screen reader users tend to use more than one technology. They may use more than one screen reader and have more than one device.

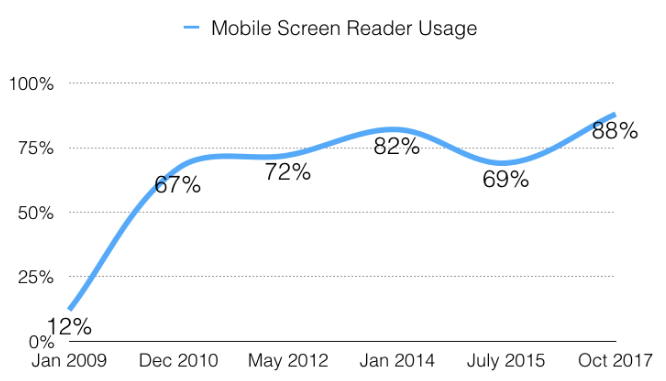

- Use of a screen reader on a mobile phone, mobile handheld device, or tablet hit an all-time high of 88% in the 2017 survey. The graph above shows that after jumping from 12% in January 2009 to 67% in December 2010, the increase to the current level has been more gradual.

- iOS devices accounted for 75% of the respondents’ mobile screen reader use and Android devices accounted for 22%.

- 54% of respondents indicated that their use of mobile or tablet screen readers was about the same as their use of desktop or laptop screen readers. 34% said they used the desktop or laptop screen reader the most.

Navigating and Searching

Screen readers offer users a variety of ways to navigate and find content on a website. Here are some data that show current trends.

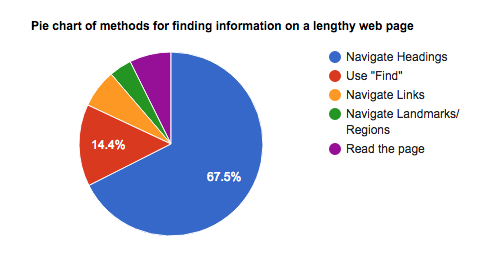

- When trying to find information on a lengthy web page, the strong favorite at 68% was navigating through headings.

- Navigating through links and landmarks ranked third and fourth, behind use of the “Find” feature, which was preferred by 14% of respondents.

- When asked how often they navigate using ARIA landmarks and regions the “Sometimes” option received the greatest number of responses (29%).

- Responses indicating frequent use (“Often” or “Whenever they are available”) of landmarks and regions has continually decreased from 44% in January 2014, to 39% in July 2015, to 31% on this survey.

- Users prefer that sites use a single first level header containing the document title.

Problem areas

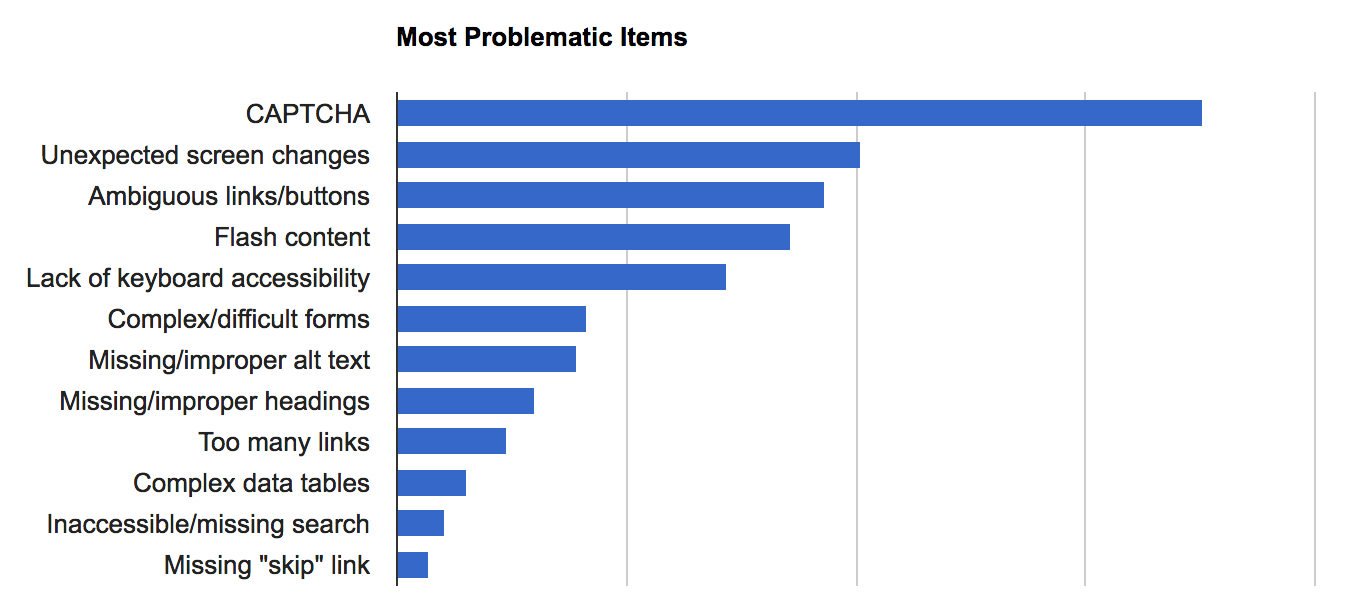

Survey respondents were asked to identify and rank their top three problem areas from a list of items. In the report on the findings of Screen Reader User Survey #7, it was noted that the order of the items in the list of most problematic issues has changed little over the years.

There were five issues that stood out as more prevalent than the others:

- By far, the most vexing issue was reported to be “CAPTCHA” fields intended to distinguish actual human site visitors from bots. It’s not clear whether this reflects continued widespread use of image-based CAPTCHAs, or the depth of frustration they cause when encountered.

- Ranked as second in importance, “Screens or parts of screens that change unexpectedly” was the one item noted as having moved up in the rankings from fifth place in the prior survey. This was attributed to more complex and dynamic sites, which are designed to provide a richer visual experience for sighted visitors.

- The presence of links or buttons with confusing or ambiguous text (i.e., “click here” or “read more”) rounded out the top three issues, followed by inaccessible Flash content and lack of keyboard accessibility.

The remaining items on the list are as follows:

- Complex or difficult forms

- Images with missing or improper descriptions (alt text)

- Missing or improper headings

- Too many links or navigation items

- Complex data tables

- Inaccessible or missing search functionality

- Lack of “skip to main content” or “skip navigation” links

Take-away messages

There is lots of information in WebAIM Screen Reader Survey #7, far more than I have summarized above. Just from the three topic areas presented, though, there are some valuable bits of information to be gleaned:

- Don’t assume that low-vision and blind visitors are sitting at home with their desktops and laptops. They are taking technology with them, just as other internet users are.

- Use meaningful semantic markup for your headers.

- Make sure your “Find” field is easy to locate and is properly labelled.

- Remove any CAPTCHA that requires users to solve a problem from your site. The more modern reCAPTCHA is not free of accessibility barriers, but is a significant improvement.

- Make your site easy to navigate and accessible to keyboard users. Screen reader users are not likely to be using a mouse.

We all want to make the web a better place, and of course we all want our own website to be better than the others. By maintaining and promoting awareness of the needs of all users, observing best practices in coding and content authoring we can make the web more accessible and reach a broader audience.